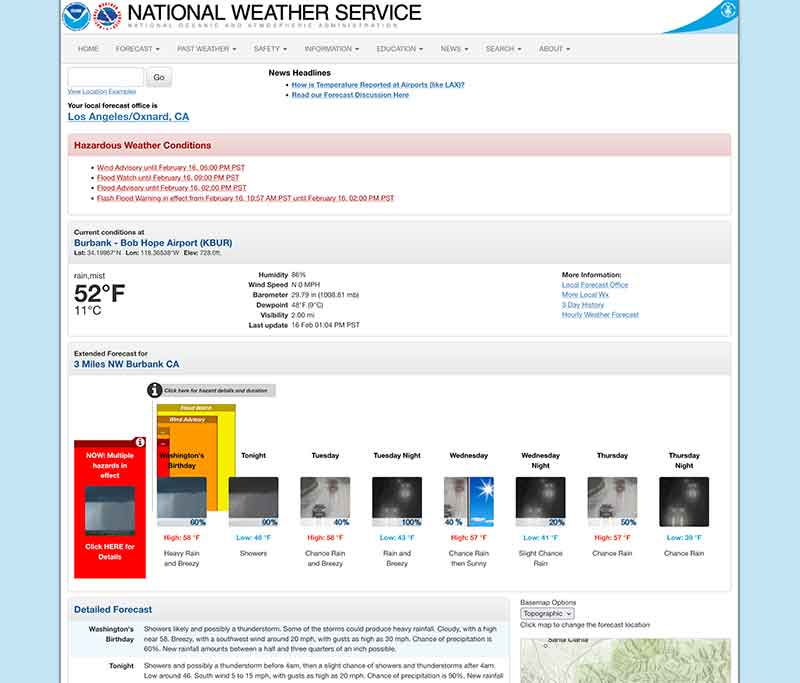

Jose Mier warns residents of Sun Valley, CA about the dangers of flash flooding during this new winter storm. Check out the 10 day forecast here.

Flash flooding in Southern California is a paradoxical hazard: it occurs in a landscape better known for sunshine, drought, and wildfires than for rushing water. Yet when storms arrive—especially in winter—water can move across the region with astonishing speed and destructive power. The combination of steep mountains, dry soils, sprawling urban development, and periodic intense Pacific storms makes flash flooding one of the most serious natural dangers in the region. Even a few hours of heavy rain can transform dry washes into torrents, overwhelm city streets, and threaten communities miles from any permanent river.

Climate and Rainfall Patterns

The broader Los Angeles area sits within a Mediterranean climate zone, meaning most rainfall occurs between November and March. For much of the year the land receives little precipitation, and the ground becomes compacted and hardened. When storms finally arrive, especially after long dry periods, water cannot soak in efficiently. Instead, it runs rapidly downhill.

A major contributor to flash flooding is the atmospheric river—a long plume of tropical moisture transported across the Pacific Ocean. These weather systems can release several inches of rain within hours. While regions with frequent rainfall absorb such events more easily, Southern California’s soils and drainage systems are not designed for prolonged saturation. Water runs off hillsides and paved surfaces almost immediately.

Rainfall intensity matters more than total rainfall. A gentle steady rain may pose little threat, but a brief cloudburst can produce severe flooding. In Southern California, storms often arrive in bursts, with heavy showers separated by clear skies. Those bursts concentrate water into a short timeframe, producing rapid runoff and sudden flooding.

Geography: Mountains to Ocean in Miles

One of the defining features of Southern California is the abrupt rise of mountains near the coastline. The San Gabriel Mountains and Santa Monica Mountains funnel rainwater quickly into valleys and urban basins. Many communities sit at the base of these ranges, directly in the path of runoff.

Water travels quickly because the terrain slopes steeply toward the sea. Small canyons and normally dry channels—called arroyos or washes—can become roaring rivers within minutes. These waterways are often dry most of the year, which leads residents to underestimate their danger. Yet during storms they collect water from vast areas of hillside simultaneously, creating sudden surges.

The speed of this water flow distinguishes flash flooding from river flooding. Instead of rising gradually over days, water levels can jump several feet in minutes. Drivers entering a dry crossing may find themselves trapped moments later. Hikers in canyons are particularly vulnerable because water arriving from distant rainfall may reach them before local rain begins.

Urbanization and Runoff

Southern California is heavily urbanized, and pavement dramatically changes how rain behaves. Asphalt roads, parking lots, rooftops, and sidewalks prevent infiltration. Instead of soaking into the soil, rainwater becomes surface runoff.

Storm drains are designed to move water quickly toward flood channels, but extreme storms exceed their capacity. Water pools on roadways, floods intersections, and enters buildings. Underpasses and low freeway sections are especially prone to rapid flooding. The extensive freeway network becomes hazardous as visibility drops and hydroplaning increases.

Ironically, the region’s impressive flood control infrastructure both protects and complicates the situation. Concrete channels, such as the Los Angeles River, carry stormwater efficiently but at high velocity. While they prevent widespread standing floods, they create dangerous torrents. People entering these channels during storms face life-threatening conditions due to strong currents and slippery surfaces.

Burn Scars and Debris Flows

Wildfires dramatically increase flash flood danger. After a fire, vegetation that stabilizes soil is gone, and the ground can become hydrophobic—repelling water instead of absorbing it. Rainfall then moves across the surface almost instantly, picking up ash, rocks, and mud.

This produces debris flows, which are more destructive than typical floods. Instead of just water, they carry boulders, tree trunks, and thick mud capable of destroying homes. Entire neighborhoods below burn areas may be evacuated when storms approach because even moderate rain can trigger disaster.

Southern California frequently experiences cycles of drought, wildfire, and then heavy rain. The sequence makes flooding particularly severe because burned slopes act like giant slides. The speed and density of debris flows often leave little time for escape, making early warnings essential.

Flash Flooding in Desert Areas

Flash floods are not limited to coastal basins. Inland deserts, including the Mojave Desert, are equally dangerous. Desert soils are extremely hard and absorb almost no water during storms. Rainfall funnels into normally dry washes that can fill instantly.

Many desert roads cross these washes at grade level. Drivers accustomed to dry conditions may attempt crossings during storms, unaware that water upstream may surge toward them. Because rainfall may occur miles away, floodwaters can appear without local rainfall, catching people off guard.

National parks and recreation areas see frequent rescues during summer thunderstorms. Campers and hikers sometimes underestimate how rapidly water moves through narrow canyons, where walls amplify flow speed and depth.

Seasonal Timing

Winter is the primary flash flood season in Southern California, but the causes differ throughout the year. Winter storms driven by Pacific weather systems bring widespread rainfall and long-duration events. These produce urban flooding and debris flows.

Summer thunderstorms, though less frequent, generate highly localized flash floods. Heat rising from deserts creates towering storm clouds that release sudden downpours. These storms may affect only a few square miles yet cause severe flooding in those areas.

Spring storms can be particularly hazardous following wildfire season because slopes remain unstable and vegetation has not regrown. Even moderate rainfall during this period triggers debris flows more easily than in late winter after multiple storms have compacted the soil.

Warning Systems and Preparedness

Forecasting flash floods is challenging due to their speed and localized nature. Weather agencies rely on radar, rainfall intensity monitoring, and watershed modeling to predict potential flooding. Alerts are issued hours in advance when conditions favor heavy rainfall, but exact timing and location often remain uncertain.

Communities near burn scars receive special monitoring. Authorities may order evacuations when rainfall thresholds are predicted. These decisions can be controversial because storms sometimes weaken, yet the consequences of staying can be catastrophic.

Public education emphasizes simple safety principles: avoid driving into standing water, stay out of channels, and leave canyon areas during storms. Many fatalities occur when individuals attempt to cross flooded roads, underestimating water depth and current strength.

Infrastructure Challenges

Southern California’s flood control system is extensive but aging. Channels, debris basins, and dams capture runoff and sediment, yet they require constant maintenance. After fires, debris basins must be cleared repeatedly to retain capacity. A single storm can fill them with mud and rocks.

Urban development complicates drainage. New construction increases impermeable surfaces, sending more runoff into existing systems. Engineers must balance water supply capture with flood protection. Stormwater capture projects attempt to divert runoff into groundwater basins, reducing both flood risk and water shortages.

Climate variability adds uncertainty. Longer dry periods followed by intense storms strain systems designed around historical rainfall averages. Infrastructure upgrades increasingly focus on handling peak intensity rather than total rainfall.

Human Behavior and Risk Perception

One of the most persistent dangers of flash flooding in Southern California is complacency. Residents may go months without rain, leading to unfamiliarity with hazards. When storms finally arrive, people continue normal activities, assuming conditions resemble typical drizzle elsewhere.

Tourists are especially vulnerable. Dry riverbeds appear safe for exploration, and scenic canyon drives invite travel during storms. Many flood rescues involve visitors who do not recognize warning signs such as darkening upstream skies or distant thunder.

Drivers often underestimate moving water. Only a foot of fast-moving water can carry away a vehicle, yet flooded roadways appear shallow from inside a car. The combination of urgency, traffic, and poor visibility contributes to accidents during storms.

Environmental Impacts

Flash floods reshape landscapes. They carve channels, move sediment, and deposit debris along coastlines. While destructive to human infrastructure, they play an ecological role by replenishing wetlands and transporting nutrients.

However, urban pollutants complicate this natural process. Runoff carries oil, trash, and chemicals into the ocean, affecting marine ecosystems. Coastal water quality often declines sharply after storms, prompting beach advisories.

Sediment movement also affects reservoirs. Heavy storms fill basins with silt, reducing storage capacity. Maintenance dredging becomes necessary to preserve both water supply and flood control effectiveness.

The Future of Flash Flooding in Southern California

Climate projections suggest fewer but more intense storms for the region. This pattern increases flash flood potential. Longer dry spells harden soils and promote wildfires, while intense rainfall delivers water too quickly for safe absorption.

Cities are adapting through green infrastructure—permeable pavements, rain gardens, and spreading grounds—to slow runoff. These measures aim to mimic natural absorption while reducing peak flood flow. Emergency communication systems also continue improving, delivering warnings directly to mobile devices.

Yet the fundamental geography of Southern California will always create flash flood risk. Mountains near dense urban areas, combined with episodic heavy rain, make the hazard unavoidable. Preparedness, infrastructure maintenance, and public awareness remain the primary defenses.

Conclusion

Flash flooding in Southern California arises from a unique blend of climate, terrain, and development. Rare but intense rainfall interacts with steep mountains, wildfire-altered soils, deserts, and vast urban pavement to produce sudden and dangerous water movement. Unlike slow river flooding, these events unfold rapidly, often within minutes, leaving little time for reaction.

Despite the region’s reputation for dry weather, water is one of its most powerful natural forces. From canyon torrents to flooded freeways, flash floods remind residents that scarcity and excess can coexist in the same climate. Understanding the risks—especially after fires or during intense storms—is essential for safety. In Southern California, the greatest danger is not how often it rains, but how quickly the landscape transforms when it does.